WEEK 4 FORUM JUNE25 2018

Your textbook discusses some of the issues related to using children as witnesses in court cases. There have been many studies done relating to the unreliability of eyewitness testimony in both children and adults. In the 1980’s and 1990’s, there was a series of court cases related to alleged multi-victim, multi-offender sexual and ritual abuse in day care centers across the country (the McMartin and Little Rascals cases being perhaps the most publicized).

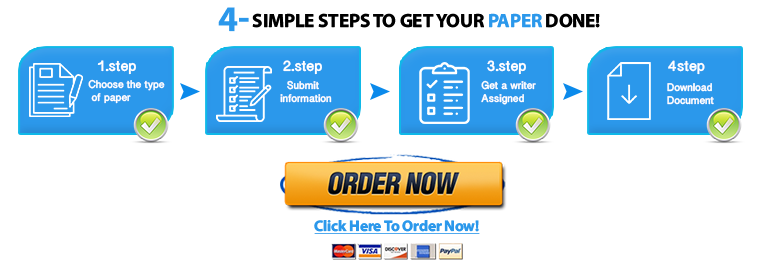

Please click on the two (2) links below and carefully read the articles:

http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/teachers-are-indicted-at-the-mcmartin-preschool

Please post thoroughly thought through answers to the questions below on the Discussion Forum for the week.

1. How do you think that investigators and therapists, in their quest to find the truth, may have contributed to children making false or exaggerated allegations in these cases?

2. What implications do these types of cases have for people who run childcare centers?

3. What are the lessons learned from these cases?

4. How should investigators and therapists proceed when a child or their parent makes such allegations?

5. How can the investigators and therapists obtain the information they need without manipulating the child’s memory, even if inadvertently.

READING

Cognitive Development

Topics to be covered include:

● Piaget’s theory of cognitive development

● Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory of cognitive development

● The information-processing perspective of cognitive development

Introduction

This lesson will look at three theories on cognitive development. The first theory we will discuss is Piaget’s. Piaget believed that children actively construct their development by adapting their existing knowledge to new situations. We will look at how this unfolds in Piaget’s four stages of development. We will then look at quite a different aspect of cognitive development in the second theory by Vygotsky. Vygotsky believed that cognitive development is mediated by sociocultural factors, and that the zone of proximal development refers to what children can achieve with and without help. The third theory we will look at is information-processing. Information-processing compares our minds to computers, and concentrates on cognitive processes, memory, reasoning and problem-solving. Finally, we will look at how our minds differ from computers because of our awareness of what we know and how we know – an awareness known as metacognition.

Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development

Photograph Jean Piaget at the University of Michigan campus in Ann Arbor.

INSPIRATION FOR THEORY

In the first lesson, we briefly touched on Jean Piaget’s theory of cognitive development. Piaget’s work on cognitive development began when he was working on IQ tests for children. He noticed that children of the same age got the same questions wrong, and that the answers of different age groups differed systematically from one another. Piaget then began studying cognitive development by giving young children problems to solve, and observing their behavior as they tried to solve these problems, and by giving older children problems to solve, and asking them to explain their thinking processes.

CONSTRUCTIVIST VIEW

The main principle of Piaget’s theory – that children actively seek knowledge – is contradictory to behaviorism which has the perspective that children passively wait for stimuli. Piaget’s theory is a constructivist view because it claims that cognitive development occurs when children build new knowledge onto their existing knowledge base. This refers to the organization of how development occurs.

SCHEMAS

The main area of cognition that Piaget focused on was the logic of how objects work and relate to one another. Schemas are concepts or elements of knowledge. While schemas get more complex as cognition develops, complexity occurs in an organized, systematic way.

The child’s increasing knowledge progressively organizes the way they interpret and interact with the world. For instance, babies use sucking to feed, then they use sucking to explore objects, both of which are physical activities which develop schemas about the world. As children grown, schemas are developed less by physical activities, and more by mental activities or operations.

ASSIMILATION

Assimilation is when experiences in the environment are interpreted through the child’s extant schema. If the extant schema is unable to assimilate the experience – or if the approach or strategy is unsuccessful, accommodation occurs, which allows the extant schema to be modified to fit the characteristics of the experience. This adaptation results in cognitive development because the schema became more complex and the child acquired knowledge.

Stages of Cognitive Development: Sensorimotor Stage

Schemas develop in four major stages. Explore these stages through this video.

As we explore these stages, keep in mind that Piaget was more concerned with the order the stages appeared in than with the age of their onset (Parke & Gauvain, 2009).

Sensorimotor Stage

In the first two years of life, children pass through the sensorimotor stage.Children build on their basic reflexes, and by the age of two, mental representations of objects and events are used to solve problems. Object permanence is a key milestone where infants learn that objects continue to exist even when they are out of sight. The sensorimotor stage comprises six substages, in which schemas are built upon and combined.

Although comprehensive, Piaget’s theory on these stages is not infallible. Baillargeon and Wang (2002) found that at around three and a half months, infants are indeed aware of object permanence but cannot display it due to limited hand-eye coordination. In addition to object permanence, developmental psychologists argue that from a very early age, infants possess core knowledge systems or a fundamental understanding of the physical world, such as object solidity whereby solid objects cannot pass through each other (Spelke, 2000). THE PRECONCEPTUAL SUBSTAGE (2-4 YEARS)

Symbolic function, which includes deferred imitation, language and imaginary play, increases. Piaget claimed that animistic thinking, or attributing life to inanimate objects, is characteristic of this stage, while subsequent research has found that at this stage, children actually can distinguish between inanimate and animate objects (Massey & Gelman, 1988). Borke (1975), also contradicted Piaget’s claim that children at this stage are egocentric or unable to see things from other people’s perspective.

Children intuitively apply mental operations without understanding the principles behind them. For instance, a child may correctly classify objects but not be able to explain why they were classified as such. At this stage, children also cannot fully grasp whole-part relationships – that is, how subsets are part of sets. Smith (1979) however refuted Piaget’s findings by experimenting with simpler questions which children correctly answered. THE PRECONCEPTUAL SUBSTAGE (2-4 YEARS)

Symbolic function, which includes deferred imitation, language and imaginary play, increases. Piaget claimed that animistic thinking, or attributing life to inanimate objects, is characteristic of this stage, while subsequent research has found that at this stage, children actually can distinguish between inanimate and animate objects (Massey & Gelman, 1988). Borke (1975), also contradicted Piaget’s claim that children at this stage are egocentric or unable to see things from other people’s perspective.

Semilogic occurs because at this stage, children have not grasped reversibility – for instance, what the result would be if the liquid was poured back into the short glass. They also cannot grasp the means by which the state was obtained, and only focus on the end result – the child only assimilated the higher liquid level but not the transfer from the wider to the narrower glass. Lastly, centration refers to how children can only focus on one dimension at a time – the heights of the liquid levels but not the widths of the glasses.

This stage of development is criticized because the age at which children understand conservation varies according to their experience with such concepts (Rogoff, 2003). For instance, children from communities in Mexico where adults make clay pots, understand conservation far earlier than most Western children (Price-Williams, Gordon, & Ramirez, 1969).

This finding raises questions about the relationship between cognitive development and cultural practices, and the generalizability of Piaget’s findings. Just as Piaget defined intelligence as the capacity to adapt to the environment (Parke & Gauvain, 2009), we can see that cognitive development is intimately intertwined with the cultural environment, and thus differs in each cultural context. Dasen (1984) therefore argued that cognitive skills develop according to their usefulness in our everyday lives.

Birth to 1 month

Basic Reflex Activity: Infants only look at objects that are in front of them, and involuntary reflexes become more voluntary.

1 to 4 months

Infants still have no concept that objects exist on their own. For instance, if an object is dropped, they will not follow its path as it falls. Infants repeat behaviors related to their own bodies that they find pleasurable – for example, finger sucking.

4 to 8 months

Infants begin to be aware of object permanence, and they repeat actions on external objects – for example, shaking a rattle, searching visually for the rattle if it is dropped or watching its path as it falls.

8 to 12 months

Infants develop intentions towards objects and combine schemas to achieve these goals. For instance, an infant may have to move one object out of the way to reach another. Problem-solving thus begins.

12 to 18 months

Infants are now aware of object permanence, and use trial-and-error methods to solve problems and learn about objects. Infants will for example drop objects from different heights to see what happens to them.

18 to 24 months

Infants can find objects that have been hidden as object permanence is fully acquired. They use mental schemas rather than physical trial-and-error to solve problems. Symbolic capability emerges in the infant’s use of language and deferred imitation.

~ scroll for more ~

Stages of Cognitive Development: The Preoperational Stage

In the preoperational stage, children develop the capacity to represent experiences and objects symbolically through words, gestures and images. This capacity develops over two substages.

THE PRECONCEPTUAL SUBSTAGE (2-4 YEARS)

THE INTUITIVE SUBSTAGE (4-7 YEARS)

Piaget proposed that children in the preoperational stage are semilogical.

· SEMILOGICAL

·

Beginning around the age of eleven or twelve, the formal operational stage is characterized by the capacity to consider many dimensions of a problem, flexible, complex thought processes, abstract thinking and mental hypothesis testing (Kuhn & Franklin, 2006). Individuals in this stage are able to apply logical concepts to problem-solving, think about philosophy and consider alternatives that are not observable.

Kuhn and Franklin (2006) argue that not even all adults reach this level of cognitive development. Furthermore, not all cultures or even groups within Western society emphasize abstract, logical reasoning (Moshman, 1998).

· REVERSIBILITY

· CONSERVATION

· ROLE OF CULTURE

Think back to the video you watched at the beginning of this section on Piaget’s stages of development. One scene showed an experiment in which blue liquid was poured from a short, wide glass into a tall, narrow glass. The child knew it was the same liquid, that is, that the quality was the same, but the child was unable to understand that the quantity was still the same because it had changed shape. Semilogic thus refers to how children in the preoperational stage cannot conserve the quantity of objects if they are converted, but can conserve their quality.

Stages of Cognitive Development: The Stage of Concrete Findings

· CONCRETE OPERATIONS

· FORMAL OPERATIONS

Children pass through the concrete operational stage between the age of seven to twelve. They grasp reversibility, conservation and can assimilate more than one dimension of a problem simultaneously. However, problems can only be solved if they are tied to concrete reality. As such, problems posed verbally cannot be solved, whereas if the components of problems are physically present, they can be solved. Critics argue however, that this may be more a function of memory. Piaget also proposed that children correctly classify objects in this stage, but researchers have found that classification capacity occurs far earlier and in a far more sophisticated manner than Piaget thought (Cohen & Cashon, 2006; Rakison, 2007).

Piagetian Concepts and Social Cognition

Social Cognition

Piaget’s work sparked ideas in other researchers about the development of social cognition. The first idea is that as children develop, they begin to differentiate themselves from others. This includes recognizing themselves in a mirror for the first time at around the age of two. It also includes understanding their own motives, values and psychological experiences, and by around the age of eleven, they start to have an integrated, complex view of themselves and their role in society (Harter, 2006).

Moral Development and Prosocial Behavior

Another idea is that children are able to understand others’ perspectives as they become less egocentric. This is key in moral development and prosocial behavior. Theory of mind is the third idea, and refers to how children come to understand the mind and people as psychological beings. It includes topics such as dreams, deception, beliefs, desires, needs, distinguishing between appearance and reality, and insight into others’ psychological states.

Knowledge Check

1

Question 1

According to Piaget, if a child can correctly organize pictures of animals and birds into their respective categories, but not explain why they categorized them as such, the child is in which stage?

The semilogical stage.

The stage of formal operations.

The preoperational stage.

The sensorimotor stage.

I don’t know

One attempt

Submit answer

You answered 0 out of 0 correctly. Asking up to 1.

Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory of Cognitive Development

Let’s begin this section by watching a video about the differences between Piaget’s and Vygotsky’s cognitive theories.

‹›

· Lev Vygotsky

We have noted that Piaget’s cognitive theory does not consider cultural and social influences on cognitive development, whereas Lev Vygotsky’s theory does. Vygotsky grew up amid social tumult in Russia in the early twentieth century, and he noticed the enormous impact this had on people (Kozulin, 1990).

As a result, Vygotsky focused on how children develop their inherited capabilities by interacting with more experienced people in their culture. Since Vygotsky saw development as occurring socially, he focused on the importance of language, how children interact with others, and the symbols and psychological tools used in a culture to promote development. He referred to these as mediators. Mediators are culture specific.

Knowledge Check

1

Question 1

Recall the example of the child with the blue liquid, where the child was able to conserve the quality but not the quantity of the liquid. Please select the two correct answers relating to this example.

Vygotsky would have seen this as an opportunity for scaffolding rather than as a discrete stage.

Vygotsky saw this as semilogic, while Piaget would probably explain this as development from elementary to higher mental functions.

Vygotsky would most likely have tested this assumption on children from various cultural backgrounds, rather than generalizing it to a stage of development.

In terms of the zone of proximal development, Vygotsky would have attributed the child’s inability to conserve quantity to her inherited capabilities.

I don’t know

One attempt

Submit answer

You answered 0 out of 0 correctly. Asking up to 1.

The Information-processing Perspective of Cognitive Development

The way a computer processes information is analogous to the way information-processing theories view human cognitive development. Both computer and human mind are organized systems that use rules of logic to process, symbolically encode, analyze and apply information from the environment. While neither can use all types of information, both have the flexibility to discard unnecessary information and improve their processing capabilities. Human minds however, can consider a wider range of problems, but are not as fast as computers at processing information.

According to Siegler and Alibali (2005), the information-processing approach to cognitive development is based on four assumptions:

THINKING

INFORMATION PROCESSING

COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT

TASK ANALYSIS

We will now look at two main information-processing models.

MULTISTORE MODEL

CONNECTIONIST MODELS

NEO-PIAGETIAN THEORIES

Cognitive Processes

Cognitive processes describe how information is acted on by the mental system. There are four major cognitive processes.

· MENTAL REPRESENTATION AND CODING

· STRATEGIES

· AUTOMATIZATION

· GENERALIZATION

Mental representation and coding refers to how relevant information is distinguished from the masses of information we are exposed to, and transformed into mentally stored information or mental representations.

Executive Control Processes

The prefrontal cortex guides how strategies are used to process information through executive control processes. Children’s knowledge base about the problems they are trying to solve also determines how they will go about solving the problem. For instance, certain children may have very useful knowledge on how to use certain computer programs to solve complex problems.

Developmental Changes

As children develop, their concentration and memory spans improve, and they learn to attend to what is relevant and develop plans of action. Processing speed also increases with development as children recognize words faster and apply a broader range of strategies more readily. For instance, if a large amount of information needs to be memorized, older children will break it into meaningful chunks or organize it into categories or relationships to remember more easily.

Knowledge Check

1

Question 1

Please select the following two correct statements.

The information-processing approach is in no way similar to Piaget’s approach to cognitive development.

The multistore model states that our working memory is stored in the sensory register.

Executive control processes determine how we process information.

Mental representations refer to information that is stored mentally.

I don’t know

One attempt

Submit answer

You answered 0 out of 0 correctly. Asking up to 1.

Reasoning and Problem-Solving

‹›

· SOLVING PROBLEMS

Every day we need to solve problems to achieve goals. These may be simple, like deciding what to eat and who to see, or they may be complex, such as completing school assignments and resolving conflict. Problem-solving consists of identifying a goal and the steps to reach the goal, as well as how to overcome obstacles. We will now discuss four problem-solving strategies or mechanisms that children learn that enable them to process information more efficiently.

Solving Problems Using Cognitive Tools

· COGNITIVE TOOLS

· SCRIPTS

· COGNITIVE MAPS

· SYMBOLIC TOOLS

Cognitive tools or external aids, like maps, calendars and language, support intelligent action by enhancing our actions. An analogy of this is how we use tools like screwdrivers and hammers. How difficult would it be to drive screws and nails into walls without screwdrivers and hammers? It would be very difficult. We will now look at three cognitive tools that enable us to function more easily.

Solving Problems Using Deductive Reasoning

Deductive Reasoning

Piaget focused a lot on how children use logic to develop his theory of cognitive development. Deductive reasoning is a kind of logic that looks at conclusions that are based on a set of statements or premises. Syllogisms are a kind of deductive reasoning that bases conclusions on a major premise and a minor premise. For instance: All dogs are animals. All poodles are dogs. Therefore, all poodles are animals.

Transitive Reasoning

Transitive reasoning focuses on quantitative information that follows an ordered sequence – for instance, if Peter is taller than Chris, and Chris is taller than Joe, who is the tallest? Children younger than six or seven are generally unable to deduce answers from this kind of information. However, four-year olds are able to organize objects in order of size if presented in a familiar or simple form, such as in pictures (Goswami, 1995).

Hierarchical Categorization

Hierarchical categorization or class inclusion is the abstract arrangement of concepts from the specific to the general. For instance, not all dogs are poodles but all poodles are dogs. Studies have shown that children begin to develop this ability at a very young age – perhaps as young as one year (Mandler & Bauer, 1988).

Numerical Reasoning

Numerical Reasoning

Numerical reasoning enables children to use numbers to reason and solve problems, and is a particularly important aspect of schooling. Piaget’s principle of conservation is an important factor in numeracy, as it relates to how children understand that the value of a set does not change even if it appears to. Recall the video on Piaget’s developmental stages at the beginning of the lesson, in which the young girl counted the number of coins in a row, but then thought that there were more coins when the row was spread out.

Numeracy Principles

Gelman and Gallistel (1978) outlined five numeracy principles children develop. These include:

1. Each object can only be counted once.

2. A number can be assigned to represent the total of a set.

3. Numbers are always assigned in the same order.

4. Objects can be counted in any order.

5. These principles apply to any group of objects.

Children as young as three may be able to apply some of these rules, or they may only be able to apply them to a limited set of numbers – for instance from one to five. As development progresses, children are able to apply all the rules and to larger sets of numbers.

Mediators

Research confirms the role of sociocultural mediators in cognitive development. For instance, Miller, Smith, Zhu and Zhang (1995) suggest that language impacts mathematical ability, whereby Chinese children have superior mathematical skills because the numbering system in Mandarin is more easily comprehended than the numbering system in English.

Metacognition

Humans have an awareness of how we solve problems and control our cognitive processing. This knowing about knowing is referred to as metacognition. When children understand their cognitive capacity as well as the task, they are able to adapt their strategies to enhance their cognition and successfully achieve the task. For instance, older children have an awareness of how much they know, and that they will not learn well when tired or unwell.

Development of Metacognition

Knowledge about the task is one aspect of metacognition. As metacognition develops, children are able to assess their own state of knowledge in relation to the tasks they need to complete, so they can obtain the requisite knowledge. For example, younger children tend not to realize when they need more information to complete tasks, and four-year olds understand that more complex tasks take more effort (Wellman, 1978).

Knowledge about Strategies

Knowledge about strategies is a second aspect of metacognition. For instance, children know that association and external aids, such as making notes, can aid memory (Wellman, 1977). As children get older, they become more aware of which strategies are most appropriate and effective for the task at hand. Metacognition is also about being aware of when a strategy is ineffective and changing it. Interestingly, Carr and Jessup (1995) note that adults do not even always have this capacity.

Knowledge Check

1

Question 1

Please select the two correct statements.

An analogy of cognitive tools is an instruction booklet for a new appliance.

The two components of metacognition are premises and conclusions.

The effectiveness of an individual’s problem-solving is a function of their reasoning, which is a function of their cognitive development.

I don’t know

One attempt

Submit answer

You answered 0 out of 0 correctly. Asking up to 1.

Conclusion

This lesson on cognitive development covered three main areas. The first area looked at Piaget’s theory of cognitive development, in which we explored the four stages of cognitive development and the various substages. Although Piaget’s theory is useful and comprehensive, we did critically analyze it. The second area we covered was Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory of cognitive development, in which the zone of proximal development is a core concept. The third area we explored was the information-processing approach. We looked at the different information-processing models and how logical and numerical reasoning are key factors in problem-solving. We lastly looked at metacognition which refers to knowing about knowing.

KEY TERMS

References

Baillargeon, R., & Wang, S. (2002). Event categorization in infancy. Trends in Cognitive Science, 6, 85–93.

Bauer, P. J., Wenner, J. A., Dropik, P. L., & Wewerka, S. S. (2000). Parameters of remembering and forgetting in the transition from infancy to early childhood. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 65(4), No. 263.

Bauer, P. J., & Wewerka, S. S. (1997). Saying is revealing: Verbal expression of event memory in the transition from infancy to early childhood. In P. W. van den Broek, P. J. Bauer, & T. Bourg (Eds.), Developmental spans in event comprehension and representation: Bridging fictional and actual events (pp. 139–168). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Berk, L. E. (1992). Children’s private speech: An overview of theory and the status of research. In R. M. Diaz & L. E. Berk (Eds.), Private speech: From social interaction to self-regulation (pp. 17–53). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Berk, L. E., Mann, T. D., & Ogan, A. T. (2006). Make-believe play: Wellspring for development of self-regulation. In D. G. Singer, R. M. Golinkoff, & K. Hirsh-Pasek (Eds.), Play-learning: How play motivates and enhances children’s cognitive and social-emotional growth. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Borke, H. (1975). Piaget’s mountains revisited: Changes in the egocentric landscape. Developmental Psychology, 11, 240–243.

Brown, A. L. (1994). The advancement of learning. Educational Researcher, 23, 4–12.

Carr, M., & Jessup, D. L. (1995). Cognitive and metacognitive predictors of mathematics strategy use. Learning and Individual Differences, 7, 235–247.

Chen, Z., Sanchez, R. P., & Campbell, T. (1997). From beyond to within their grasp: The rudiments of analogical problem solving in 10- and 13-month-olds. Developmental Psychology, 33, 790–801.

Cohen, L. B., & Cashon, C. H. (2006). Infant cognition. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Series Eds.), & D. Kuhn & R. S. Siegler (Vol. Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 2. Cognition, perception, and language (6th ed., pp. 214–251). New York, NY: Wiley.

Daniels, H., Cole, M., & Wertsch, J. V. (2007). The Cambridge companion to Vygotsky. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Dasen, P. R. (1984). The cross-cultural study of intelligence: Piaget and the Baoulé. International Journal of Psychology, 19, 407–434.

DeLoache, J. S., & Smith, C. M. (1999). Early symbolic representation. In I. E. Sigel (Ed.), Development of mental representation: Theories and applications (pp. 61–86). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Gelman, R., & Gallistel, C. R. (1978). The child’s understandingof number. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Goswami, U. (1995). Transitive relational mappings in 3- and 4-year-olds: The analogy of Goldilocks and the Three Bears. Child Development, 66, 877–892.

Goswami, U., & Brown, A. L. (1990). Higher-order structure and relational reasoning: Contrasting analogical and thematic relations. Cognition, 36, 207–226.

Harter, S. (2006). The self. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Series Eds.), & N. Eisenberg (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of child psychology (6th ed., Vol. 3, pp. 505–570). New York, NY: Wiley.

Hitch, G. J., & Towse, J. N. (1995). Working memory: What develops? In F. E. Weinert & W. Schneider (Eds.), Memory performance and competencies: Issues in growth and development (pp. 3–21). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Kozulin, A. (1990). Vygotsky’s psychology: A biography of ideas. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kuhn, D., & Franklin, S. (2006). The second decade: What develops (and how?). In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Series Eds.), D. Kuhn & R. Siegler (Vol. Eds.), Handbook of child psychology, (Vol, 2, 6th ed., pp.953–994). New York, NY: Wiley.

Mandler, J. M., & Bauer, P. J. (1988). The cradle of categorization: Is the basic level basic? Cognitive Development, 3, 247–264.

Massey, C. M., & Gelman, R. (1988). Preschooler’s ability to decide whether a photographed unfamiliar object can move itself. Developmental Psychology, 24, 307–317.

Miller, K. F., Smith, C. M., Zhu, J., & Zhang, H. (1995). Preschool origins of cross-national differences in mathematical competence: The role of number-naming systems. Psychological Science, 6, 56–60.

Moshman, D. (1998). Cognitive development beyond childhood. In W. Damon (Series Ed.), & D. Kuhn & R. S. Siegler (Vol. Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 2. Cognition, perception, and language (pp. 947–978). New York, NY: Wiley.

Parke, R., & Gauvain, M. (2009).Child Psychology: A contemporary viewpoint (7th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Price-Williams, D. R., Gordon, W., & Ramirez, M., III. (1969). Skill and conservation: A study of pottery-making children. Developmental Psychology, 1, 769.

Rakison, D. H. (2007). Fast tracking: Infants learn rapidly about object trajectories. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11, 140–142.

Richland, L. E., Morrison, R. G., & Holyoak, K. J. (2006). Children’s development of analogical reasoning: Insights from scene analogy problems. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 94, 249–273.

Richland, L. E., Zur, O., & Holyoak, K. J. (2007). Cognitive supports for analogies in the mathematics classroom. Science, 316, 1128–1129.

Rogoff, B. (1990). Apprenticeship in thinking: Cognitive development in social context. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Rogoff, B. (2003). The cultural nature of human development. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Siegler, R. S. (1996). Emerging minds: The process of change in children’s thinking. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Siegler, R. S., & Alibali, M. W. (2005). Children’s thinking (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Smith, C. L. (1979). Children’s understanding of natural language hierarchies. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 27, 437–458.

Spelke, E. (2000). Core knowledge. American Psychologist, 55, 1233–1243.

Sperling, G. (1960). The information available in brief visual presentations. Psychological Monographs, 74.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological functions. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wellman, H. M. (1977). Preschoolers’ understanding of memory relevant variables. Child Development, 48, 1720–1723.

Wellman, H. M. (1978). Knowledge of the interaction of memory variables: A developmental study of metamemory. Developmental Psychology, 14, 24–29.