Role in Disaster & Emergency Communication Interoperability

I’m studying for my Communications class and need an explanation.

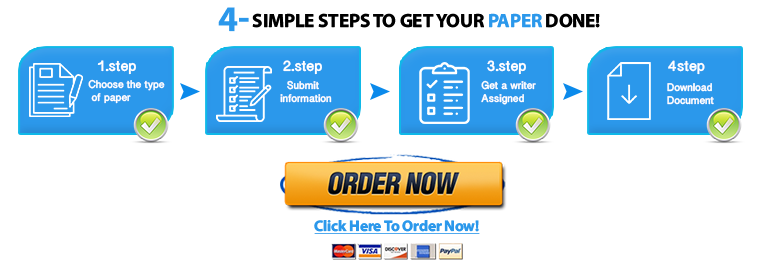

I have a question that need to be answer with 500 words I have but the the document you should read to answer it

alos i have provided to different answers so you can take a look at it and paraphrase little.

the question

Answer the question critically-How does the NECP attempt to assure Disaster and Emergency Communication Interoperability?

Remember to explain the why and the how!

the document

Answer 1

NECP finds its purpose in enabling the nation’s emergency response community to communicate and share information across technologies in real-time (CISA, n.d.). This interoperability not only exists between various technologies but also between multiple stakeholders within the community, including federal, state, local, territorial, tribal, and private sector (CISA, n.d.). To ensure that each of the involved parties is receiving the right message at the right time, the NECP provides a structured set of goals to which organizations should aspire and multiple assistive operational guides depending on the stakeholder and desired communication technology.

Since the establishment of the NECP in 2008 (Department of Homeland Security, 2008, p. 1), there have been significant improvements in interoperable capabilities. Understanding that disaster communication methods require a whole community approach is a start that allowed for establishing statewide strategic planning based upon the outlined priorities and goals (CISA, n.d.). Due to this improvement, one of the most critical ways that NECP assurers interoperability is by learning from the past. The Communications Interoperability Performance Measurement Guide allows statewide interoperability coordinators (SWICs) to gauge progress in attaining or sustaining interoperability capabilities (Department of Homeland Security, 2011, p. 2). No matter what position one holds for employment, measurement of progress is integral to improvement. The same goes for communication interoperability. Through planning and training, and eventually, use, governments, and emergency response leaders can identify breakdowns in their communication systems and effectively adjust for improvement. Emergency responders must be able to make decisions quickly, and communication issues prevent that from happening. By measuring the success of communication systems, interoperability is assured, and disaster response results are more effective.

CISA. (n.d.). Emergency Communications Guidance Documents and Publications. Retrieved October 8, 2020, from https://www.cisa.gov/emergency-communications-guid…

CISA. (n.d.). National Emergency Communications Plan. Retrieved October 8, 2020, from https://www.cisa.gov/necp

Department of Homeland Security. (2011, April). Communications Interoperability Performance Measurement Guide. Retrieved October 8, 2020, from https://www.cisa.gov/sites/default/files/publicati… Interoperability Performance Measurement Guide_0.pdf

Department of Homeland Security. (2008, July). National Emergency Communications Plan. Retrieved October 8, 2020, from https://dem.nv.gov/uploadedFiles/demnvgov/content/…

answer 2

David McComb

Oct 8, 2020 at 8:01 PM

-How does the NECP attempt to assure Disaster and Emergency Communication Interoperability?

The premise is clear: When multiple agencies come together, the success of their collective action hinges upon direct and secure lines of communication at all levels of organization (Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency [CISA], 2019). Daily-use infrastructure will not be immune to the unfolding disaster. A surge is user activity rendered cell phones and landlines unusable to first responders immediately after the Boston Marathon bombing in 2013 (Office of Emergency Communication [OEC], 2013). Employing up to date technology and acknowledging gaps is part of creating channels for messaging must be refined before any event (CISA, 2019).

I view the evolution of technology combined with the restriction of financial resources as one of the challenges in uniting organizations or jurisdictions. The Metropolitan Transporation Agency (MTA) in New York City still relies on a landline system termed the “six wire. (Jenkins, 2003: Nessen, 2020). The six-wire name refers to how it originally tied conversations together for the subway company, track workers, transit police, signal workers, car equipment workers, and station agents (Nessen, 2020).

The MTA has built different methods of inter-agency communication over the subsequent, a redundancy that was credited as a strength on September 11 when transit operations retained the ability to communicate (Jenkins, 2003). The NECP places emphasis on “real-time” communication (CISA, 2019). The time lag in human point-to-point conversations in the MTA system has an exploitable feature known to emergency workers and most New Yorkers. If the NYPD is chasing you, switching from street-level to subway, or vice-verse, crosses jurisdictions and radio frequencies, buying you an advantageous couple of minutes.

The NECP asserts that 911 systems need to adopt geographical information systems (GIS) in place of addressing. During my service with FDNY EMS, I experienced the advent of cellphones in a landline centered system. Emergency call texts always came with an ANI/ALI. The ANI/ALI gave you the address logged with the phone line, even if it was a phone booth. Address data is crucial for hang-ups and open lines. One of my initial experiences with a cellphone generated 911 call was wandering Prospect Park for close to an hour looking for someone with a broken ankle. I see the clear value in shifting over to the use of GIS. I am interested in hearing from any of our current EMS if your systems use GIS. (I’ve heard rumor of a Philly firehouse that relies on a fax machine tipping over a soda can as the station alarm.)

Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency. (2019). National emergency communications plan. Washington, D.C.: Department of Homeland Security.

Jenkins, B. M. (2003). Saving City Lifelines: Lessons Learned in the 9-11 Terrorist Attacks [MTI Report 02-06]. San Jose, CA: Mineta Transportation Institute Publications.

Nessen, S. (2020, October 6). One last shift on the MTA’s “Six Wire,” where vital information is relayed old school. Gothamist. Retrieved from https://gothamist.com/news/one-last-shift-on-the-m…

Office of Emergency Communication. (2013). Emergency communications case study: Emergency communications during the response to the Boston marathon bombing. Washington, D.C.: Department of Homeland Security.